My comments are included in Bloomberg Law today, in Angélica Serrano-Román's article, "Bourbon, Monet, and Tax Credits Find a Niche Market in Bankruptcy" (link below). This is the passage:

Most recently, a Claude Monet ‘Water Lilies’ painting from the collection of bankrupt hedge fund manager George Weiss showed up on Inforuptcy, a subscription website for professionals and distressed-asset investors that scans court documents and sale motions from the government’s online docket system and converts them into listings. Think Craigslist, only for bankruptcy assets. [...]

It lacks the complexity seen in Monet’s more significant later paintings of ‘Water Lilies,’ said David Shapiro, an art adviser with experience appraising the collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts. They have richer color and “are more resolved paintings, with this painting looking more sketch-like by comparison,” he said.

As of late November, nine Monet paintings of ‘Water Lilies’ have sold at public auctions for more than $50 million, including buyer’s premium, he added.

The bankruptcy court ultimately approved the sale of Weiss’s Monet in October for $36.5 million. There were no competing bids after another deal fell through, when a potential buyer couldn’t secure funding.

The art world has crossed into bankruptcy before, most notably through Detroit’s “Grand Bargain,” launched to prohibit the sale of works from the then city-owned art institute to pay off debt and to help raise funds to protect pensions in 2014. [...]

PRMA blog post: The Art Market Is Moving Fast: Here’s Why Appraisals and Insurance Matter More Than Ever

Following my recent webinar, Private Risk Management Association (PRMA) summarized the program in a blog post, "The Art Market is Moving Fast: Here's Why Appraisals and Insurance Matter More Than Ever".

Their blog post covers topics in the presentation including:

-- A market of extremes

--The rise and fall of emerging artists

--The risk of underinsurance

--Appraisal standards

--The expanding world of collectibles

--The benefits of staying proactive

Drawing from the webinar, PRMA has also assembled an Art Market Volatility Watchlist, alerting brokers, underwriters, collectors, and their advisors to some key points regarding shifting values in the present market.

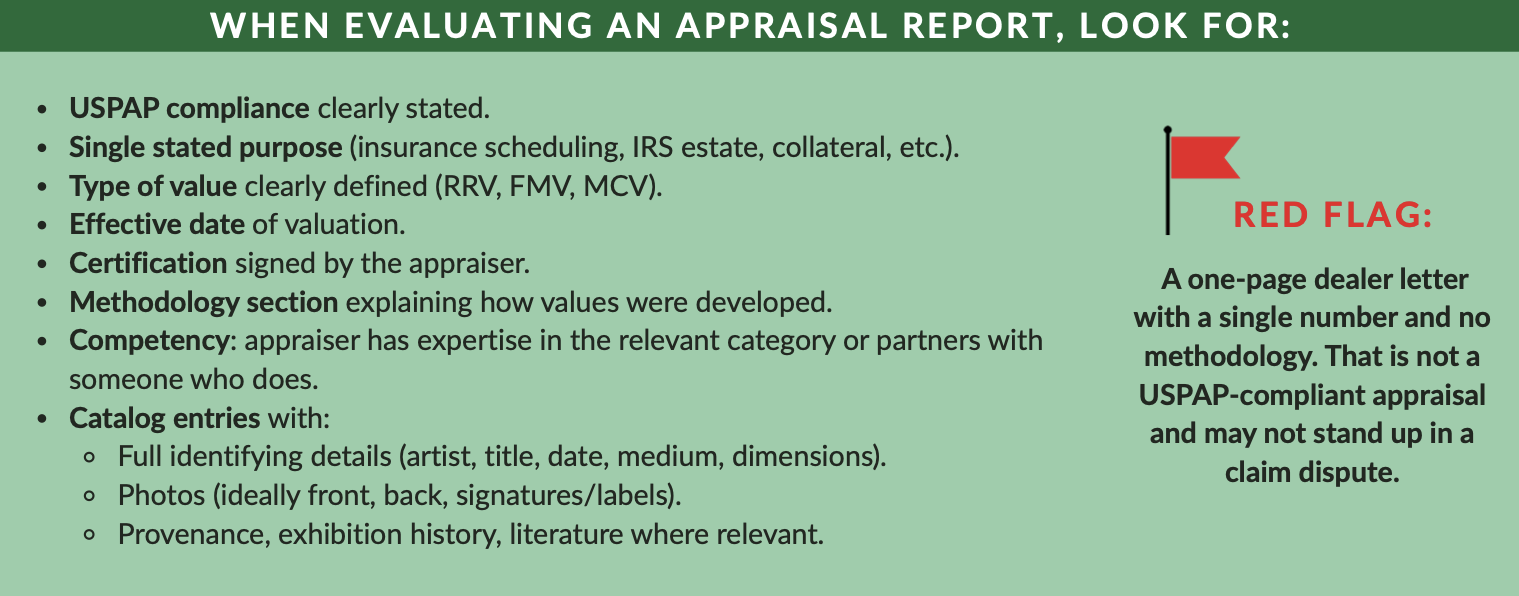

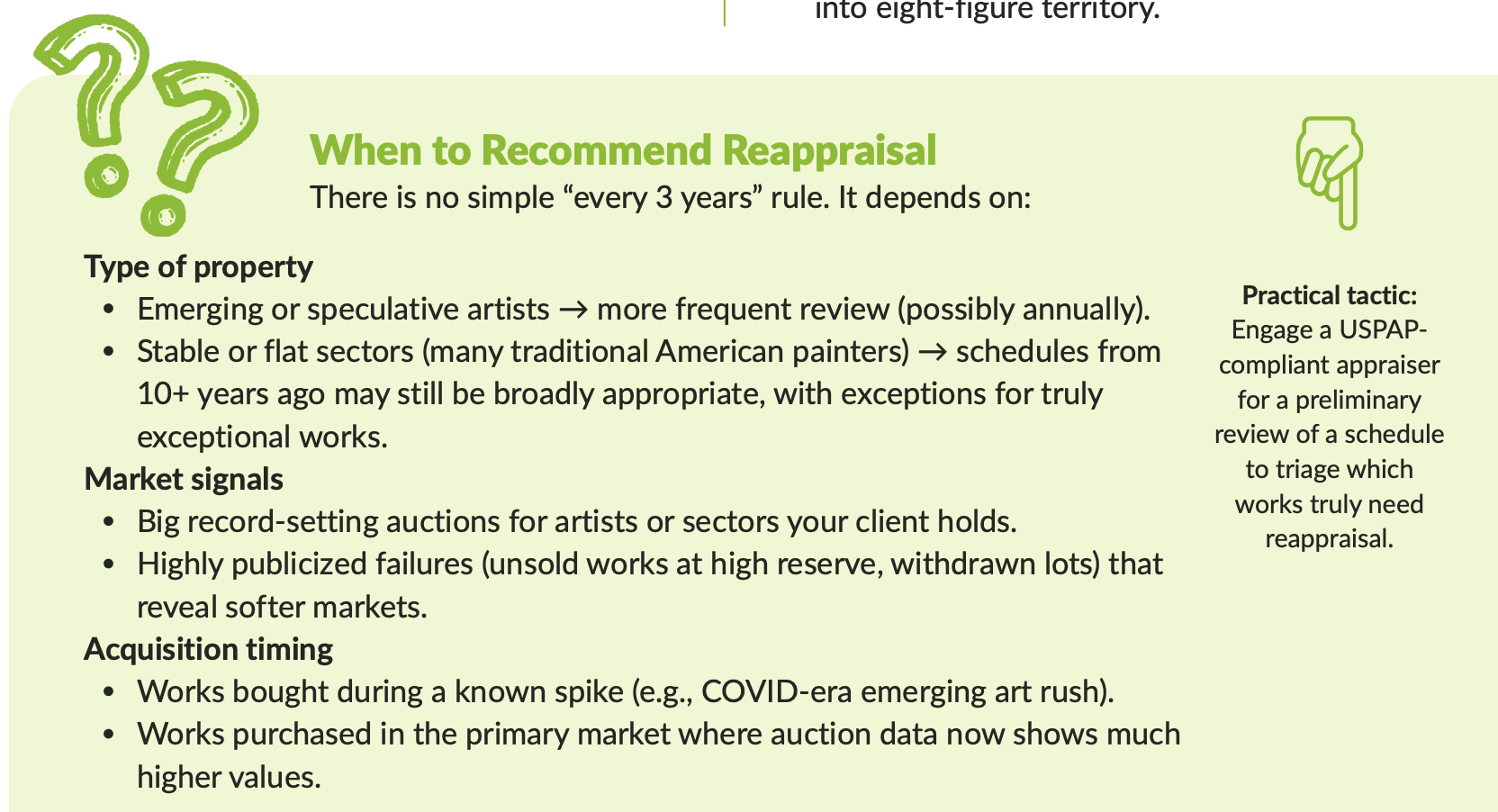

Recommendations in this Watchlist include the following, concerning what to look for in an appraisal report and when works of fine art should be reappraised for insurance purposes.

Shook, Hardy & Bacon: Art Law Bulletin: Art Basel Miami Beach: An Art Appraiser’s Perspective

It was a pleasure to contribute to the December 2025 edition of Shook, Hardy & Bacon's “Art Law Bulletin.” This feature, assembled by Channah M. Norman, Tristan L. Duncan, and Alicia J. Donahue, is titled Art Basel Miami Beach: An Art Appraiser’s Perspective. My contribution is as follows:

The Artsy Art Basel Miami Beach wrap article says that the highest sale at the fair was Andy Warhol’s “Muhammad Ali” (1977) for $18 million at the Lévy Gorvy booth, and ARTNews says that the most expensive work on offer at the fair was a 1979 untitled Joan Mitchell on offer from Richard Gray Gallery for $18.5 million, though the report from Art Basel itself states that David Zwirner sold its Mitchell, “Sunflowers” (1990-91), for $20 million.

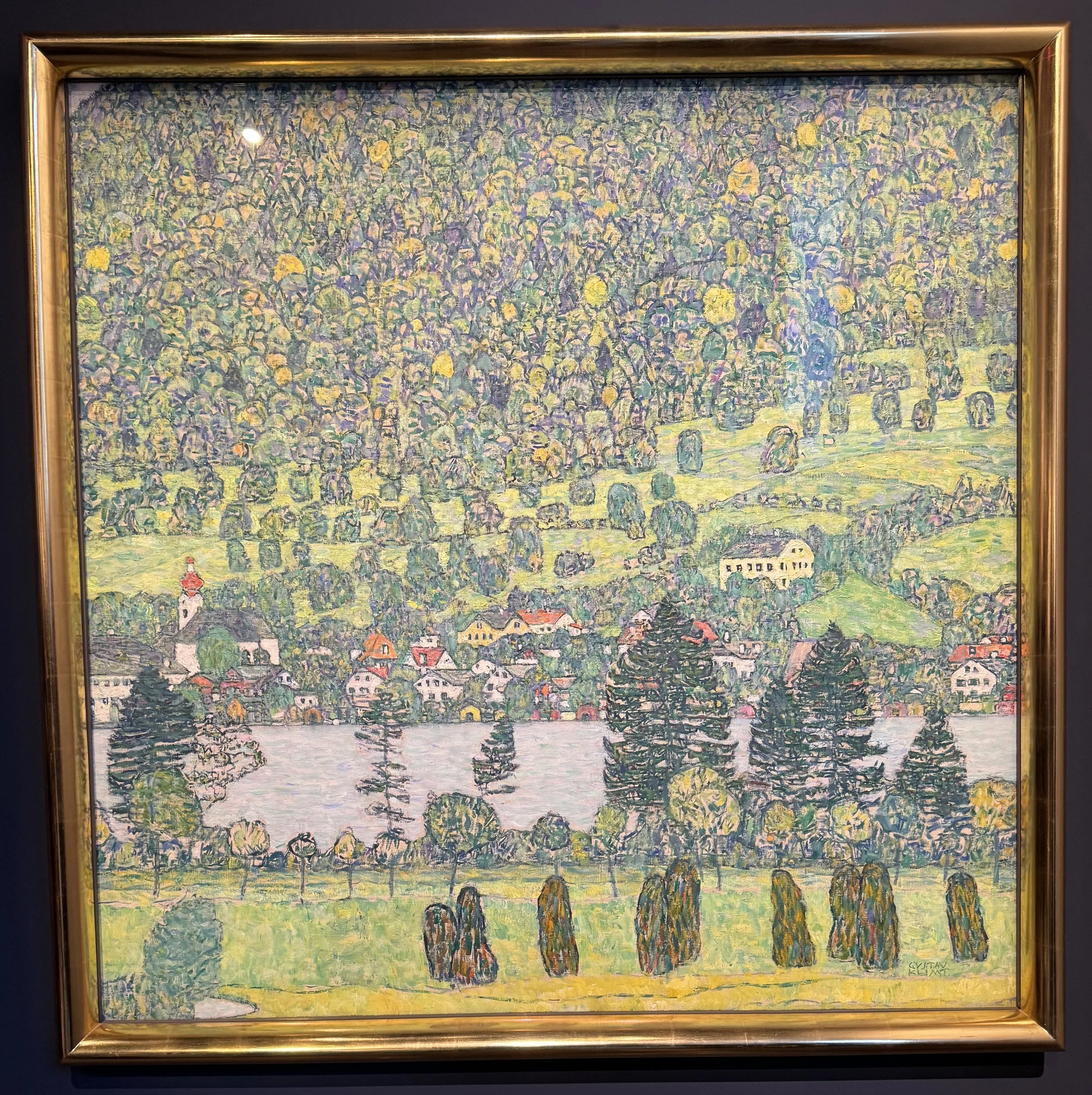

In fact, none of the above were the highest offerings at the fair. Gagosian was offering Picasso’s “Surreal Boy with a Basket” (1939) for $22 million, and Van de Weghe was offering Jean-Michel Basquiat’s “Onion Gum” (1983) for $21.5 million. These were the highest asking prices that I observed at this edition of Art Basel.

To my knowledge, the press has not commented on whether the Picasso or the Basquiat sold at the fair, and indeed, this may never be known, considering that dealers, being protected by the Privacy Rule in the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, have no legal obligation to disclose any of their realized prices at art fairs or otherwise, even while local laws may require them to conspicuously publish asking prices at the point of exposure. Although dealers may offer information about realized prices to journalists or in exit surveys issued by a fair, doing so is voluntary. Consequently, reports of completed transactions at art fairs are necessarily approximate at best, unlike published results of sales at public auction, which offer clear indicators of the market.

Whether or not the most expensive works on offer at Art Basel found buyers that week, it is worth noting that even at this fair, which is the largest and generally considered the most significant U.S. art fair, the highest end of offerings capped out around $20 million, which could be considered within range for a major art fair, notwithstanding occasional higher outlier offerings. This level is considerably lower than the high end of the auction market.

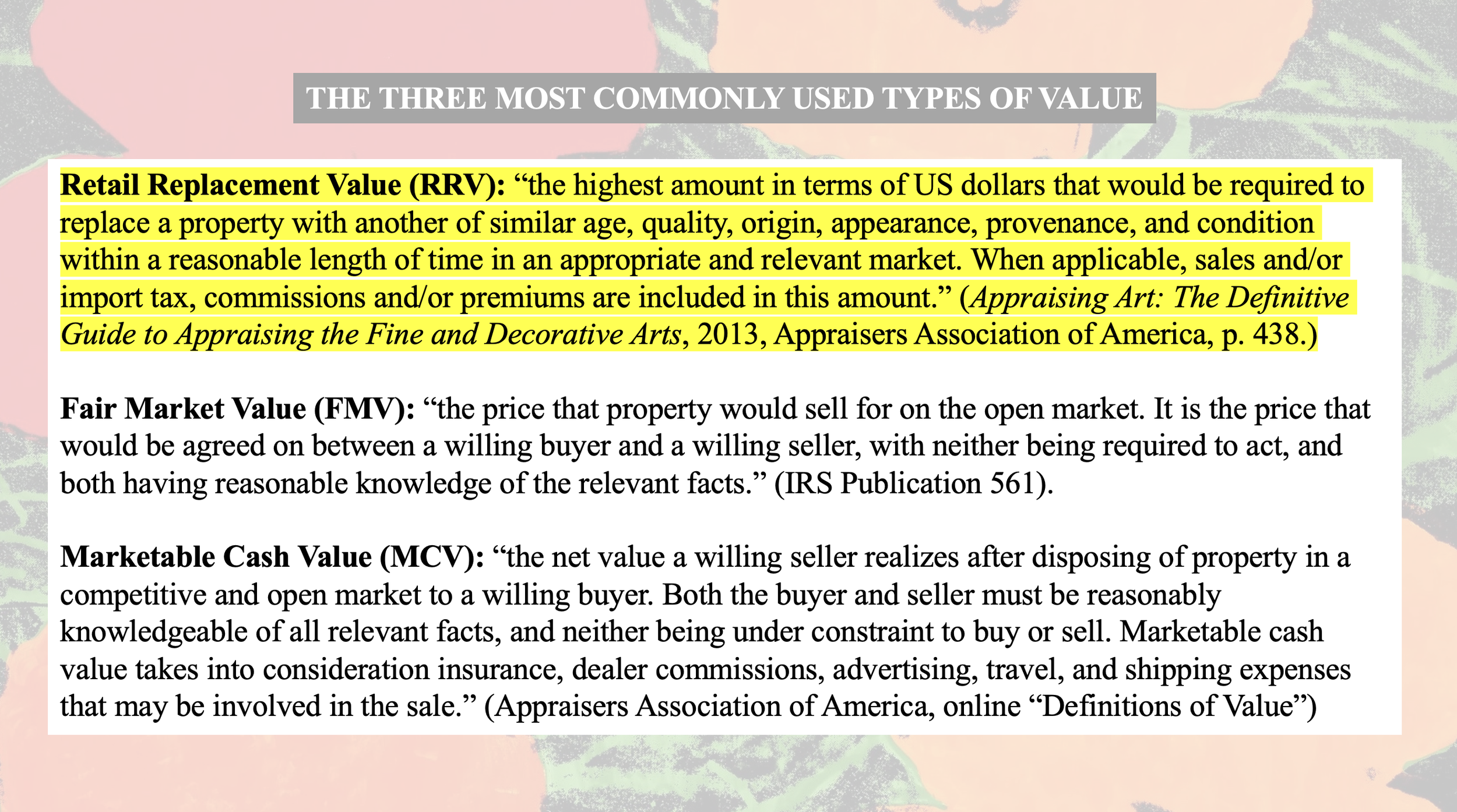

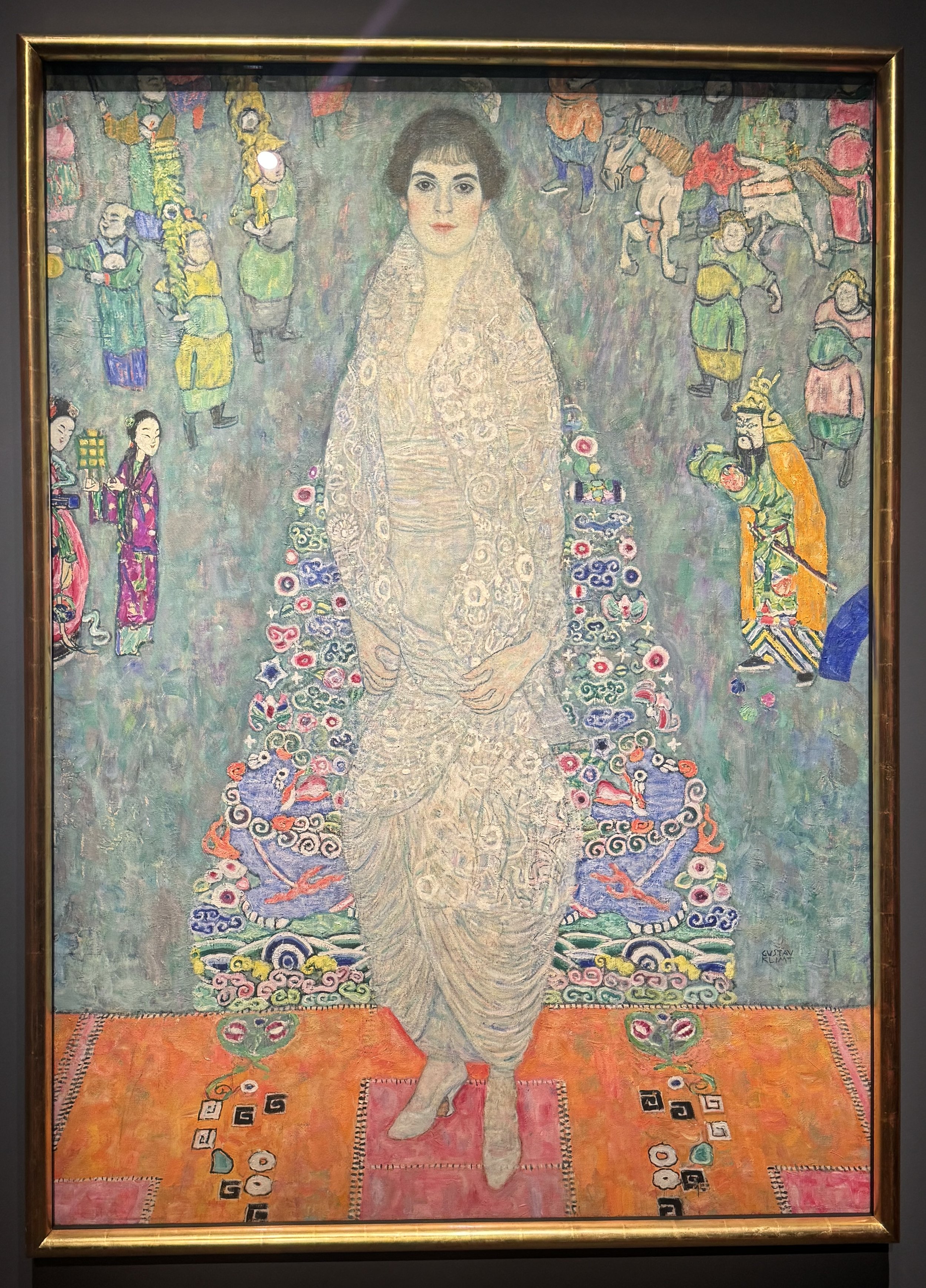

By comparison, in the November 2025 marquee auctions in New York, 19 lots fetched prices in excess of $18 million each (including buyer's premium), among which 10 lots sold above $40 million. Among these, six lots sold above $50 million, namely three Klimt paintings, a van Gogh, a Rothko, and a Kahlo. Klimt’s “Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer” fetched $236.4 million at Sotheby’s, the second highest auction price ever realized for a work of art and the highest for a work of modern art at auction.

Adjacent to the fine art sphere, the high end of the auction market has continued to witness phenomenal results in December 2025, most notably the sale of a Fabergé egg for $30.2 million at Christie’s in London and the sale of François-Xavier Lalanne's Hippopotamus Bar for $31.4 million at Sotheby’s in New York, an all-time auction record for the design sector.

The soaring high end seen in November was in no small part driven by circumstance: among the top 10 lots in the November 2025 auctions, 75% of total sales (by value) comprised estate property, the timing of which is beyond anyone's control. However, there were also significant discretionary sales among the highest ($18 million+) tier, including the sale of the Kahlo, “El sueño (La cama),” for $54.7 million, which set the record for any female artist at auction and any Latin American artist at auction. We simply did not see such offerings at Art Basel.

Anecdotal as they may be, reports indicated brisk sales in the middle market at Art Basel Miami Beach this year. One may speculate as to whether the buoyant auction market of November 2025, in which overall totals far surpassed those of equivalent sales in recent seasons, primed the mood for the fair such that private sales were easier to effect. Although the record sale of a $236 million Klimt from the Lauder estate may have very little direct correspondence to the relative volume of six-figure transactions that dealers may make at the fair, it is indeed reasonable to speculate that mood may have been a factor, though shifts in market behavior often owe to a variety of cultural and economic factors, and direct causation can be difficult to trace.

"Icons" at Sotheby's: A private sales story

Sotheby's Icons exhibition, currently on view in New York, is intended as a mini compendium of key auction sales at the house over the decades. And yet, ironically, it is in large part a story about private sales -- and above all, those which brought four masterpieces to the collection of Citadel CEO and mega-collector Ken Griffin, notwithstanding silence in the exhibition wall text about the post-auction sales histories of these paintings.

The first is Basquiat's 1982 Untitled head, which sold to Yusaku Maezawa at Sotheby's in 2017 for $110.5 million, setting an all-time auction record for any American artist (surpassed at Christie’s in 2022 with the $195 million sale of Warhol’s 1964 Shot Sage Blue Marilyn). Maezawa’s $200 million private sale of this Basquiat to Griffin was reported in Artnet News in May 2024, but the story remained publicly uncorroborated until now.

The $200 million price attained for Shot Sage Blue Marilyn was in no small part benchmarked by another private Griffin purchase of a Warhol painting included in “Icons,” namely the closely related Shot Orange Marilyn (1964), originally purchased at Sotheby’s by S.I. Newhouse for $17.3 million in 1988 and much later, in 2017, sold to Griffin for approximately $200 million.

Also in Icons is De Kooning’s Interchange (1955), which sold at Sotheby’s for $20.7 million, but, market-wise, is perhaps best known for its 2015 private purchase by Griffin from music mogul David Geffen for a reported $300 million in a deal reported also to include the $200 million purchase of Pollock’s Number 17A (1948). The $300 million purchase of the De Kooning was the highest known price paid for a work of art in any market, and today, it is still second only to the Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci (and/or workshop), which fetched $450.3 million at Christie’s, NY in 2017.

The fourth significant Griffin loan to Icons is Jasper Johns’s False Start (1959), which sold for $17 million at Sotheby’s in 1988 and later, in 2006, was sold by Geffen to Griffin for a reported $80 million. It is worth considering what the painting might bring today, nearly 20 years later.

Irrespective of any possible such price growth, these four paintings comprise a total of approximately $780 million in total realized private sales, none of which is mentioned in the exhibition wall text. This is not a criticism; to the contrary, it was a pleasure and a rare opportunity to be able to see these major paintings, among others, assembled together for what may be the only time, but it’s also worth observing that the unspoken epicenter of this exhibition allegedly about auction sales, is indeed something quite apart than that.

Also not to miss in Icons are brilliant paintings by Kahlo, Klimt, Mondrian, Sargent, Still, and others, all looking their best in the Breuer building, itself a masterpiece.

PRMA webinar: Takeaways on art appraisal for insurance

Thank you to Private Risk Management Association (PRMA) for hosting a webinar that I led yesterday, "The Art Market, Appraisals, and Insurance: What Brokers Need to Know Now." The presentation was a 50/50 talk, first a bird's eye view of the current art market, then a "nuts and bolts" discussion about some of the most salient aspects of art appraisals for insurance purposes.

A few takeaways for brokers and underwriters:

1. Appraisers whom you or your insureds engage should be USPAP-complaint, competent in the relevant area(s), and ideally hold membership in one of the major appraisal organizations such as the Appraisers Association of America.

2. USPAP (the only appraisal standards authorized by US Congress) comprise a set of requirements and guidelines designed to ensure impartial, objective, independent appraisals, with certain baselines established for diligence, methodological thoroughness, record keeping, ethical conduct, and reporting.

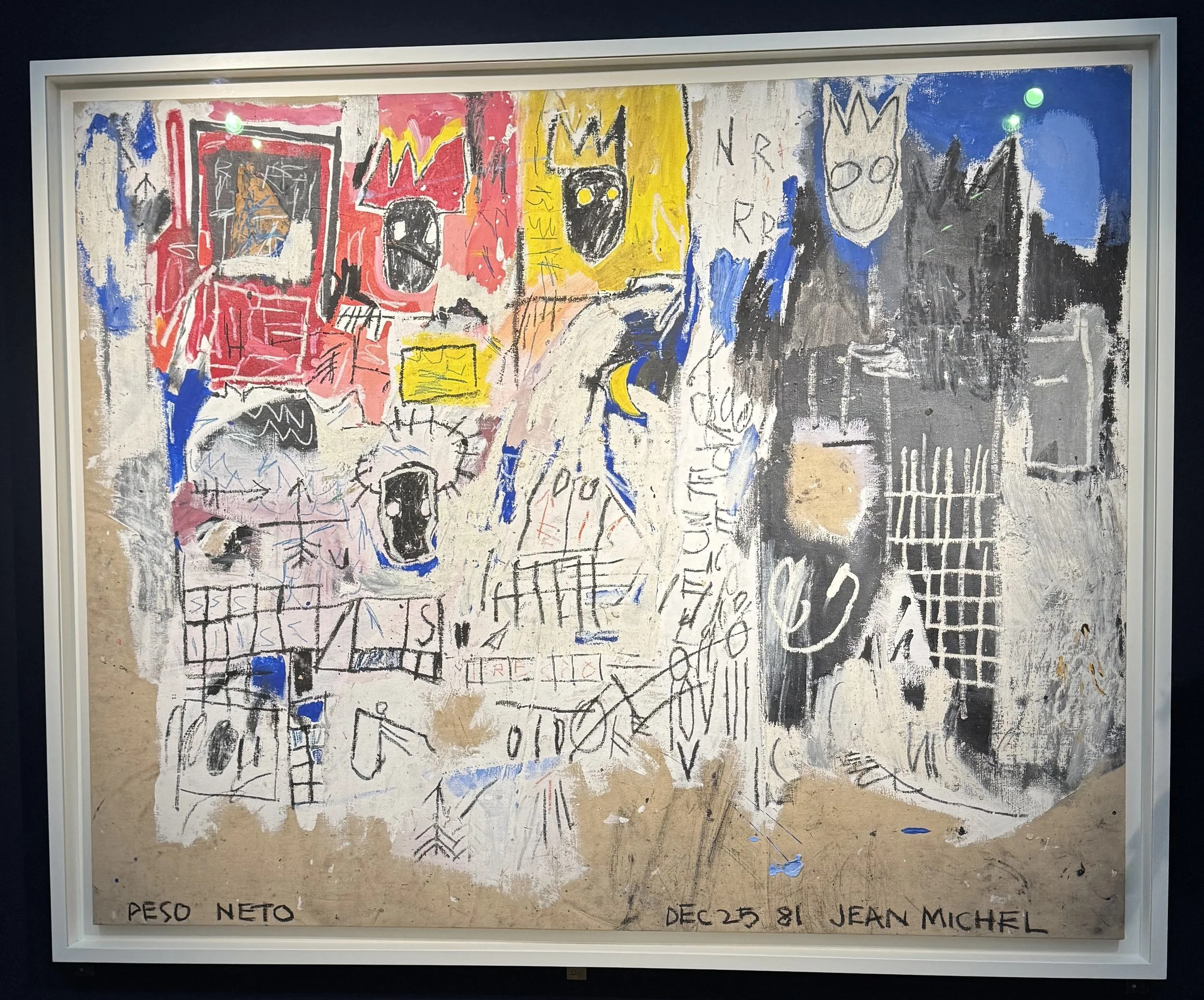

3. There are different types of value. The same work of art will have a different valuation depending on the *type* of value.

4. For insurance scheduling purposes, your insureds should commission appraisals that assess Retail Replacement Value, which is defined as “the highest amount that would be required to replace a property with another of similar age, quality, origin, appearance, provenance, and condition within a reasonable length of time in an appropriate and relevant market.”

5. There is no net relationship between the types of value, especially between Fair Market Value and Retail Replacement Value. This depends enormously on the type of art in question. For some works, the difference between FMV and RRV may be 20%, and for other works, it may be 10x.

6. There is no set timeline for when to reappraise art. This depends on the type of art. For example, a collection of emerging art should probably be considered for reappraisal for insurance purposes more frequently than a collection of traditional American art.

Comments in ARTnews on Cecily Brown

My comments on this week's auction offerings of Cecily Brown paintings are included in Daniel Cassady's article for ARTnews, "Christie's 21st-Century Evening Sale Totals $123.6 M. and Sets a Few Records" about last night's sale:

Most surprising perhaps was Cecily Brown’s It’s not yesterday anymore, which received three bids before auctioneer Yü-Ge Wang—who took over for Meyer after the Edlis-Neeson lots were complete—pulled the work.

As art adviser and appraiser David Shapiro reminded ARTnews after the sale, Brown’s record was reset on Tuesday evening at Sotheby’s after a 10-minute showdown brought High Society (1997–98) from a starting bid of $4 million to a total of $9.8 million. “Market buoyancy notwithstanding, this example suggests that discernment with respect to quality may be a lesson preserved, at least in the meantime, from the last two years,” Shapiro said of Wednesday evening’s pass on It’s not yesterday anymore.

November 2025: High end of the auction market in New York

When it rains, it pours. After a dry spring season in which no works sold above $50M in the marquee sales, and only two (the Monet and Mondrian) sold above $40M (plus the Canaletto six weeks later), the fall auctions are looking very different, with 9 lots poised to sell in this territory or above.

At Sotheby's, the three Klimt paintings have "estimates on request," respectively, of $150M+ for the portrait, and $70M+ and $80M+ for the two landscapes. The Kahlo is estimated at $40-60M, and the Basquiat at $35-$45M.

Christie's has the Rothko with an "estimate on request" in the region of $50M, the Monet at $40-60M, and the Picasso and the Hockney each estimated in the region of $40M (plus there's an exemplary, potentially record-breaking Canaletto on preview for a Feb. sale in Classic Week).

It's a given that the November Evening Sale totals will appreciably exceed May 2025 totals, and yet, one must be careful not to over-extrapolate larger market trends from such changes given that the high end is often a supply-driven market segment, with sales totals tied largely to circumstance. Many of these consignments are estate property, the timing of which is beyond control.

WEBINAR: The Art Market, Appraisals, and Insurance

Please join me on December 9th at 1pm for a webinar, “The Art Market, Appraisals, and Insurance: What Brokers Need to Know,” hosted by the Private Risk Management Association (PRMA). Registration here.

Quote in Artsy about auction fees

My comments are included in Maxwell Rabb's article published today in Artsy. The article provides a clear and useful summary of the fees associated with buying and selling art at auction.

My quote is about the vendor's commission:

A seller’s commission is a fee charged to the seller by the auction house for its services. A seller’s commission is usually charged at a rate between 5 and 10 percent.

Seller’s commissions vary from lot to lot depending on an array of factors: the value and desirability of the work, the competitiveness of the consignment, the seller’s relationship with the auction house, and the financial structure of the sale (like guarantees or marketing costs). High-value or prestigious lots often receive lower or waived fees to attract them, while lower-value or riskier works carry higher commissions to cover costs.

“They’re more likely to enforce a seller’s commission on a low-value work,” said Shapiro. “For a high-value piece, they’ll do what they can to get it, since they’re probably competing against other houses.”

Some categories—like design, wine, and online-only sales—carry their own rates. Even within the same auction house, London and New York may apply slightly different terms.

Journalistic irresponsibility re. art valuation (yet again)

While I hesitate to amplify, I find it harder to sit idly in the face of another article touting artificial intelligence as a panacea to art valuation. Moreover, this salacious column is predictably written by someone (Daniel Grant) with no firsthand experience buying, selling, or appraising art, and it is perhaps unsurprisingly riddled with misinformation, inaccuracies, and elisions.

As a small selection:

1. Any responsible mention of the use of AI to authenticate Old Masters should be accompanied by an acknowledgment of its severe limitations and its potential for misattributions and dispute (lest we forget the Raphael episode).

2. Appraisers do not "set prices" -- we set ascribe values. If Mr. Grant does not know the difference, he should not be writing such an article.

3. The statement that "only a small percentage of artworks are sold at public auction" is misleading. A very significant percentage of high-value works of art are sold at auction.

4. Mr. Grant asks how insurers are "supposed to write fine art policies for collections if the appraisers they rely on have little or no access to the prices paid for artworks." It's patently absurd to contend that appraisers have "little or no access" to private realized price data, when in fact it's precisely our job to research and report on such markets. All good appraisers do this -- and insurers know (or should know) to rely on valuations performed by those appraisers. Technology will not help with this.

5. Mr. Grant uncritically quotes an AI professional who says that "A.I. can understand why and when the value of an artist's work changes over time" However, Mr. Grant curiously does not quote a single appraiser. As a reminder, AI is only as good as what it is fed. AI has neither relationships nor private knowledge, nor any real intelligence in making the necessary decisions to such a pursuit as art appraisal.

etc., etc., etc.

Chubb Art Market Update

It was a pleasure and honor to give the 2025 H1 Art Market Update talk to Chubb’s Fine Art team last week. Thank you to Laura Doyle for extending the invitation, which provided an opportunity to reflect just before the fall auction season opens in New York this week.

By many measures, the art market continued to contract significantly in 2024 (e.g., auction totals down 25%, and off by 39% for $10M+ lots), and has remained soft on the whole in 2025, and yet the total picture has been much more complex than this.

Year-to-year comparisons of totals at equivalent auctions are not fully determinative with regard to the health of a market, nor can demand necessarily be wholly assessed given the circumstantial nature of supply, whether from estates or otherwise.

Strong sales in supply-challenged markets such as Old Masters have shown strength when exemplary works have become available (e.g., Canaletto), and we have seen surges in many markets, not least Surrealism (most visibly, Magritte and Carrington), key female artists in various sectors (e.g., Dumas record), and historically undervalued collecting categories such as South Asian postwar and contemporary art, as well as the personal property markets adjacent to art such as Design and collectibles, in which a series of extraordinary records have been set.

As the consignments for November are just being announced, including those at a level not seen in the first half of the year (esp. Klimt), we can begin to forecast what the fall might look like relative to the spring.

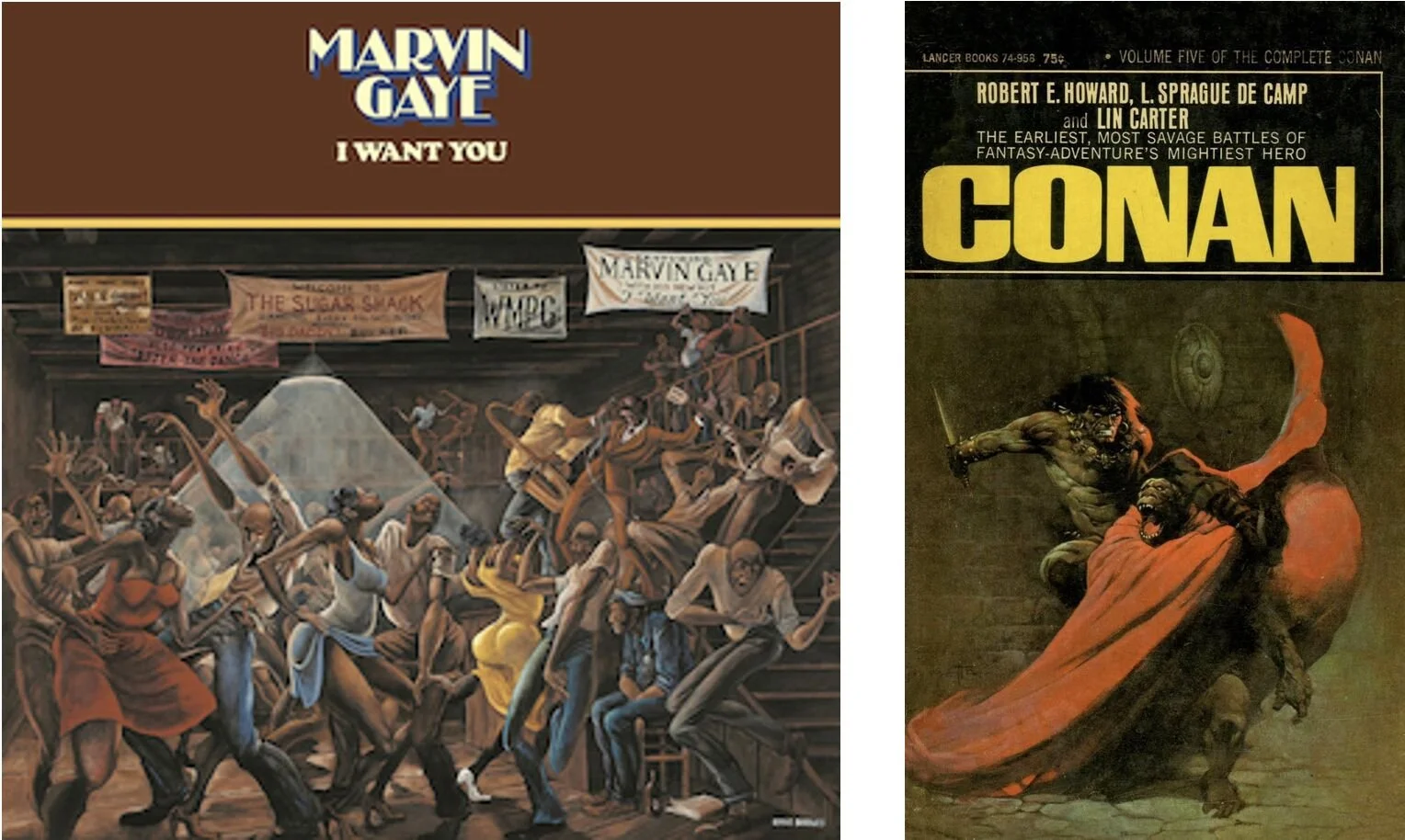

(l.) Ernie Barnes, Sugar Shack (1976) on the cover of the Marvin Gaye album, I Want You; Frank Frazetta "Man Ape" (1966) on the cover of Conan by Robert E. Howard, L. Sprague de Camp, and Lin Carter

Heritage Auctions: a record price in the market for illustration

Heritage Auctions just made another extraordinary sale, fetching $13.5M for Frank Frazetta's "Man Ape" (1966), the highest auction price ever realized for a Comic or Fantasy work of art.

In the art market, we're accustomed to the duopoly of Sotheby's and Christie's dominating the field, but it's Heritage where we've recently seen a procession of extraordinary prices at the high end of the non-art market, with records routinely set for collectibles such as sports and entertainment memorabilia.

At one level, this sale of a highly sought-after piece of illustration fits neatly within into the paradigm of recent market surges for personal property with popular cultural meanings, and outside the market for traditionally recognized high art — precisely at a moment when the mainstream art market has shown signs of softening. But this sale also opens onto larger ontological questions about what distinguishes a work of illustration from a piece of fine art.

It's the Frazetta's familiarity from mass reproduction that propelled its price not only to an artist record but to an all-genre record. However, this sale also immediately recalls the sale of Ernie Barnes's "Sugar Shack" (1976) at Christie's for $15.3M in 2022, following a bidding war that catapulted its price 70x above its high estimate and leagues above the price realized for any other work by the artist. Demand for that painting followed from its mass reproduction as an illustration for Marvin Gaye's album "I Want You."

Complicating the picture is the fact that Frazetta takes visual cues from nineteenth-century European academic painting, whereas Barnes draws on the visual language of cartoons — and yet the current marketing and institutional contexts have established the Barnes as a work of fine art and the Frazetta as a comic illustration.

Artsy quote: Inflation and the Art Market

My comments are included in Veena McCoole’s article in Artsy, “How Inflation Impacts the Art Market”:

“Prices may be up, but if money coming in is also up, that doesn’t necessarily mean a downturn in art purchasing for some,” noted art advisor David Shapiro. “People in the market for a Pablo Picasso, perhaps, aren’t as swayed by inflation and day-to-day costs.”

Reginald Marsh, Art Auction, ca. 1940

Chelsea Gallery Walk

It was a pleasure leading the Chelsea gallery in late July for Risk Strategies Company’s summer event, visiting the Robert Indiana and Alicia Kwade exhibitions at Pace Gallery, Carmen Herrera at Lisson Gallery, and William Kentridge at Hauser & Wirth with colleagues in the artist legacy space. It was a great conversation and a memorable day/night.

RRV and FMV: a complex relationship

In 1972, Stephen Weil wrote the Art in America article “Prices-Right On!” in which he commented on the performance of a Parke-Bernet sale relative to pre-sale estimates: “In theory, at least, the top [high] estimate should be somewhat less, perhaps 10 to 20 percent, than the price a gallery would ask for a similar painting or sculpture. (For its higher price, the gallery may provide a range of works from which to choose, a chance to try works at home on approval, guarantees of authenticity, and condition, and even extended payment terms and the right to make a later exchange).”

In many (if not most) market sectors, it is still expected that dealers will command a premium relative to the auction market for similar property, for reasons such as those noted by Weil. The precise ratio, however, which is far from standard, is a constant source of challenge and inquiry for appraisers. The compexity can be highlighted, for example, when an appraiser is assigned to assess both the Retail Replacement Value and the Fair Market Value of works of art.

RRV, as defined by the Appraisers Association of America, is the “highest amount … that would be required to replace a property with another of similar age, quality, origin, appearance, provenance, and condition within a reasonable length of time in an appropriate and relevant market.”

FMV, by contrast, is “the price that property would sell for on the open market. It is the price that would be agreed on between a willing buyer and a willing seller, with neither being required to act, and both having reasonable knowledge of the relevant facts.” (See: IRS Publication 561). [NB: Notwithstanding its source, FMV and this definition of it are commonly used in a variety of non-IRS applications.]

Sometimes the appraiser, when assessing RRV in a market with few or no available relevant comparable retail sales or offerings, must look to the auction market and extrapolate upwards, but the ratio is not necessarily a summary 10-20%, nor is it 30-40% or some other fixed range that can be applied to any property, but rather it is a ratio that is specific to each market.

Speaking broadly, the delta between FMV and RRV for the same object tends to be much smaller at the high end of the value spectrum. For example, a Rothko that sells for $50 million at Sotheby’s might only be privately marketable for slightly more than such a realized auction price. It may well be that a dealer could only reasonably offer that same painting for $55 million, and therefore, in that stratospheric market, RRV may potentially be no more than 10% higher than FMV.

Consider, then, an emerging artist whose works are offered for $20,000 in the primary market. There is ample supply, no secondary retail market, and works that are occasionally offered at auction fetch only $5,000. In such a case such as this, RRV may well be quadruple FMV.

There are innumerable examples, principally at the low end of the market, in which a secondary market price on LiveAuctioneers will only be a small fraction of the original retail price. There are many works with no secondary market history and no ostensible attainable secondary market at all. In all such cases, the difference between RRV and FMV would follow from these variances.

There are also cases in which an appraiser must assess FMV for an artist whose works have never traded in any secondary market but show promise to attain strong prices if they were to be offered. Demand as well as supply in the primary market would be likely to offer insight as to what a secondary market may hold for the artist.